Art of Change : Actor, Director and Movie Producer.

You can be sure it’s safe that you have no idea what it is, and you’re coping with Netflix’s pesky “Are you still watching?” alerts. De Niro’s not only a name — it’s an adjectival phrase. “Oh, it was very De Niro acting.” Clueless yet? Wait ‘til the end.

Here’s the guy whose issues were that he did not like acting. Nuh-uh, he had to be the thesp. Don’t ruin it all for all of the rest of u s by screwing it all up by screwing it all up, he did it.It was born on 17th of August 1943 (yes, he’s in his 80s, and no, you shall never be as funky), whose biography is like the book on ho w to screw every character that walks in thy door. Where the rest of u s can’t even set updating our résumés, he’s won Oscars since telephones had wires.

First Oscar win at Oscars be hooligan, first win? Playing young Vito Corleome in The Godfather Part II (1974) as yes good ole first-time as part of all-time all-time best of all-time screen mob boss kingpin kingpins. It’s like being asked on first internship internship and elected CEO. Raging Bull later in 1980, playing Jake LaMotta, acting with such passion it won it for him the award of Best Actor but maybe scarred very much own face off in bathroom mirror good for month. Don’t even start with Taxi Driver (1976) as in “You talkin’ to me?” Yes indeed, Bob, we be!). It set the standard so high it’s still on every “Top 10 Movie Quotes of All Time” list.

And it only gets good. Goodfellas, Casino, Heat, The Deer Hunter. Close those eyes and crash on that body of work of his, and it’s like ordering topping on your pizza – all good. And have I even talked about his funny range? Meet the Parents, Analyze This. The guy’s deadpan sophistication cutting that you’ll be rightfully condemned for watching it.

Awards, Respect, and Never Sorry

And wait for it, it keeps getting better. The guy isn’t just an interpreter of characters, people. When you were deliberating hawaiian versus pepperoni versus whatever as dinner, De Niro played A Bronx Tale and The Good Shepherd. And while thinking whether you’re heading out for jog, he co-founded the Tribeca Film Festival. Why? Because it seemed like as good of time as it would ever be to start the cultural phenomenon, I guess. Six of his films were added to the U.S. National Film Registry as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” Not one. Not two. SIX. That’s as good as it gets as far as movies go. That’s like having those baby pics of yours framed at the Louvre.

And don’t act like the awards have forgotten about the guy. The guy’s got more lifetime awards than you’ve had argyles on. AFI Life Achievement Award? Check. Kennedy Center Honors? Check. Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award? Yet another check. It’s getting to where it’s not very exciting at all bestowing De Niro with yet another award because it’s like presenting LeBron James with the basketball with the note on it that says, “You know, have you tried it before?”

And it’s more than that, the guy’s career isn’t at it’s peak. No apology tours, no “supporting character as wisheh-grandpa” set piece. No way, he’s already blowing through roles (The Irishman, anyone?) while the rest of it is going through Google on “How to transition into home work.” The kicker is, he won’t back down. Grapevine gossip he’s ordered an honorary 2025 Palme d’Or. Course he is. Robert De Niro isn’t going through the motions like playing by the rulebook, he’s breaking the rulebook. It’s an acting and passion masterclass every step of the way, every sentence, every on-camera subtlety. Shortened version? De Niro doesn’t act nearly as much as he intimidates every piece of dialogue into submission. The rest of us can only sit back and gawk in awe and wonder what we’ll Netflix next, because he’s over here showing why Hollywood’ll always tip the hat in awe. A legend? Yes. But the thing is, it underestimates. It’s Robert f-ing De Niro, and legends don’t have dictionaries attached — they redefine.

Baptized, Bohemian, and Bound for the Spotlight

Robert Anthony De Niro did not arrive in the world—he burst into it, Greenwich Village, Manhattan, on August 17, 1943—the product of parents Virginia Admiral and Robert De Niro Sr. with an artistic heritage pretty much DNA-inked. They were painters, mind you, but contemporary artists with debauched lives of melodrama. It’s as if the world looked at his family tree and declared, “This child is going to need much character development.” Nine points for the universe on that call. Spoiler alert: it did.

De Niro’s childhood was like a Broadway romance. The parents Bobby and Virginia De Niro Jr.’s romance had begun as a “meet-cute” at Hans Hofmann’s art class at Provincetown but went bankrupt after the father declared himself homosexual. Bobby Jr. was only two at the age of that plot twist, casting the rest of all of his teen years yet long past all-American suburban joy.

Growing up between bohemia neighborhoods of Manhattan with the quirky character of Greenwich Village all within and the hard-but-soft bite of nearby Little Italy, De Niro grew as a youth with annoyance and fantasy all around. Theexperimental painter father was close at hand. The alienation of it all notwithstanding, Sr. had no qualms in vetoing Bobby’s suspicious career choice of associates. “Bobby Milk,” with pale-faced face, grew as one of the hard-as-nails sons of Little Italy. Somewhere within every such family vacation dinner table, you could hear his father’s exasperated sigh.

Where religion was involved, Bobby’s life would’ve earned itself an HBO miniseries at least as long as The Sopranos. With a mom that swung back and forth between atheist and Presbyterian, with a father that quit being Catholic at age 12, with paranoid grandparents that went and baptized him anyway, De Niro was all but prophesied of playing nuanced characters. Family melodrama? Check. History of emotional depth? Check. A child baptized without parental consent would have some existential angst as a child.

Education wasn’t any less colorful. His school years resembled a game of academic hopscotch. Starting at PS 41, he briefly lit up the stage at the Dramatic Workshop as the Cowardly Lion at just ten. Then came a whirlwind tour of schools, including Elisabeth Irwin, the High School of Music & Art, IS 71, McBurney, and Rhodes Preparatory. None of them stuck. At 16, De Niro decided he’d had enough of classrooms and traded algebra for acting. His logic? “If those mediocre guys on TV can make a living, I can’t possibly be worse.” Say what you will, but the man knew how to bet on himself.

And then he not only tried acting—he enrolled. The guy was not being counseled. Here, he went at it headfirst with classes with Stella Adler, Lee Strasberg, and the Stanislavski technique and absorbed every last morsel of instruction like a sponge with the added experience of being a hard-luck street tough.

And that is the way the pale-faced Bobby Milk child running through Little Italy with suspicious associates turned into Robert De Niro, the person still forever referenced, imitated, and worshiped. The splatter-painted start, rebel school days, and wild raise all nourished the talent of acting with depth and soul. A family story turned into ticket-purchasing phenomenon. That’s an Oscar-worthy character development.

1963–1973: Bobby Milk’s Resume Before Stardom

Robert De Niro did not stroll into Hollywood and wake up a star. He worked for his upkeep, accepting parts so minimal, “blink and you’ll miss him” is generous. Some films he worked on during his early career included Encounter (1965), Three Rooms in Manhattan (1965), and Les Jeunes Loups (1968)—films so obscure, perhaps films could be installation art and not films. But, who doesn’t begin somewhere?

It began with 1968’s Greetings, a Vietnam War-set satirical comedy and De Niro’s role as a draft-evading optimist. Among them came Brian De Palma, his future professional pal. Masterpiece? No. But it paved the way for their professional bromance, and you could actually have a successful bromance on a shaky script.

And then came Sam’s Song (1969), where his character was a New York director, and then The Wedding Party (1969), filmed back in 1963 but kept under wraps for years. When its release did finally occur, critics treated it kindly, although unexpectedly, and The New York Times even labeled the film “great fun.” One can almost hear De Niro say, “finally,” under his breath.

In 1970, Bloody Mama continued the “sensitive choices” period for low-budget maven Roger Corman, during which he was one of Ma Barker’s crime sons. Critics provided courtesy accolades, calling performances “fine,” as though you could say about good diner cuisine. Then, and only then, in the dark comedy sequel to Greetings, Hi, Mom! (1970), De Niro found his groove. As a Viet war vet-movie director-virtual nipple-flasher, he brought a wild unpredictability on film upon audiences. Critics like Richard Brody raved over his “unhinged spontaneity,” courtesy code for the fact that he was wired to bust up on film.

Early ’70s saw mixed bag-type films such as Jennifer on My Mind and Born to Win (1971), and the forgettably awful crime comedy The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight. 1973 was different, however. As a baseball man stricken with Hodgkin’s disease in Bang the Drum Slowly, De Niro delivered raw vulnerability that brought raves. The Hollywood Reporter referred to him as “one of the most likable young actors,” and Variety cited his performance for a “touching” one. Even writer Mark Harris kidded that De Niro supposedly had his hands off a baseball other than perhaps during the film—but he was correct.

And then Mean Streets. Into his life emerged a young director, Martin Scorsese, who would prove to be De Niro’s lifetime artistic partner. Playing hot-headed wannabe hood Johnny Boy Civello, De Niro delivered a performance that was a critical sensation. The New York Times called it one of a kind and Pauline Kael compared him to Dustin Hoffman but “wilder.” Mean Streets launched his career, all right—shot his young leading man to the stratosphere, and preceded Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and a whole string of defining performances.

From scrounging on the fringes of indie movies to recreating on-screen passion, De Niro’s ascendance was neither elegant, nor a straightforward one. Success was neither simply his genius, nor his willingness to take the risk and make the abnormal choice, but a sprinkle of unexpected-ness. He is a legend, indeed—but let’s remember the man who brought the rookie baseball player and the crazy director forth. The raw, dirty poetry of filmmaking.

1974-1980: Scorsese + De Niro = The Men Who Made Filmmaking Look Like a Hobby

Robert De Niro. Saying the name here is accompanied by the tidal wave of cinema iconography and the type that results in one wondering whether one has achieved something spectacular with one’s miserable life either. Very few actors can become their characters so much so that performance ceases to hover in the background as performance and performance begins to resemble suspiciously reality filtered through sheer determination and ruthlessness. Every De Niro film I see is less film and more psychological case study presented with impeccable verisimilitude.

Think of The Godfather Part II. Yes, young Vito Corleone. De Niro didn’t enter Coppola’s universe of Sicilian crime families; he became their pulsebeat. Screen-tested as Michael in the first Godfather but somehow ending up instead in The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight? Embarrassing. And humiliation again evidently whets one’s appetite, because where Coppola did offer him another chance, De Niro leapt into it wholefootedly. He studied Sicilian, he projected cold-steel authority, and he won an Oscar. Oh, and tasty trivia morsel? He and Marlon Brando both won Academy Awards for playing Vito Corleone. It’s the sort of film trivia even stone-facedestestestestest mobster couldn’t help but crack a smile at.

But the audience was not grimy enough. In comes Taxi Driver. Post-Vietnam New York, neon lights, and one man’s gradual slip into madness. Travis Bickle is less walking, dysfunctional city despair mirror than character. Weight loss, gun training, do-it-yourself “You talkin’ to me?” speech––De Niro’s acting hurts because it’s depressingly realistic. Critics praised. When Travis tears open his mirror rehearsal it reveals one thing conclusively: De Niro does not uncover the psychology of a character; he constructs it, brick by tortured brick.

And then Raging Bull (1980). Self-destructive Jake LaMotta was not merely a boxing story; he was an obsession, a rage-filled study, and, I should confess, how much physical transformation an actor is capable of. Brandoing again 60 pounds and tearing loose tear-stained scenes so bestial as to make one wince, De Niro received his third award. There is one scene in which LaMotta’s fury reaches pitiful desperation, and one is breathless. Few performances do a better job of anticipating razor-sharp conclusions to human fallibility than that one.

But De Niro wasn’t content to just be the ’70s and early ’80s gritty antihero poster child. He showed range, too. Take The Deer Hunter, where he invested so much emotional richness in his character that he left audiences deeply unsettled by the manner in which Vietnam ravaged the human psyche. Travis Bickle was anarchy incarnate, Michael in The Deer Hunter was quiet strength in the face of unbearable trauma. Another Oscars nomination? Naturally.

And if you’re already thinking he’s tragedy and gangsters, do not forget New York, New York (1977). De Niro even learned how to play the saxophone to deliver his performance in it. That’s right: just as soon as you’ll feel proud at managing to get through another thing, just remember that De Niro practiced sax for hours for a role in a film even critics could not decide if it were a masterpiece or flop. But if did or did not make it to theaters, he gave his performance with obsession finely calculated to perfection.

Robert De Niro’s performances are not a string of acts but a lesson in what it’s like when the entirety of an actor’s existence is committed to his work. Whatever he’s playing — mobsters, boxers, or broken men gazing into voids — De Niro’s not acting. He’s inhabiting those men long enough to make us agitated in ways that still linger with us even after we’ve left his movie.

perhaps his true legacy is Robert De Niro. He does not headline films; he makes you see, feel, and question. He is actor enough that his film lingers with you deep inside you even long after the Dudz. He’s left his mark on film and our collective unconscious. Bad to the man who began with a crew that couldn’t shoot straight.

1981 – 1991: Robert De Niro in the ’80s and ’90s: Redefining the Hollywood Star

Robert De Niro of the ’80s and ’90s was not just an actor—he created a new blueprint for what a Hollywood star was. While other stars were happy with what they had, De Niro cast himself in roles as slickly as he’d slip into his favorite Italian-cut suit, testing the boundaries of machismo. And with each, he made his mark with his own, unmistakable swagger.

His “True Confessions” (1981) role had been an odyssey of a priest through family crisis as he and his detective brother investigated murder. His double casting with Robert Duvall had been so total that Vincent Canby in The New York Times credited it as “a single performance.”

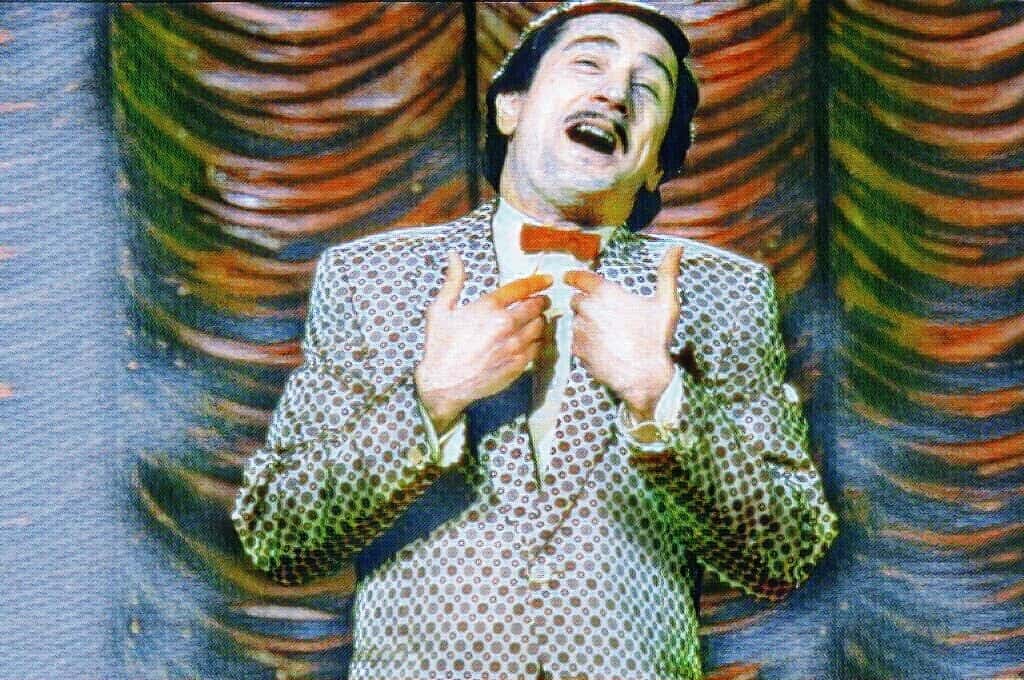

Then came “The King of Comedy” (1982), in which De Niro stumbled and staggered around as would-be comedian Rupert Pupkin. It bombed at the box office (it netted $2.5 million from an $19 million investment), but convinced critics.

Once again resized by “Once Upon a Time in America” in 1984, as an epic crime drama. American critics shunned the U.S. version, stripped by the producers, which tore the protean multileveled narrative into pieces, whereas Cannes audiences cheered it for 15 minutes.

De Niro flirted half-heartedly with rom-com in “Falling in Love” (1984) with Meryl Streep. Mannered to excess and overlooked. And then there was the bizarre “Brazil” (1985), dystopian horror fantasy hellworld that initially people were bowled over by but turned out to be such.

He portrayed a redeemed mercenary turned missionary in “The Mission” (1986). Cinematography won an Academy Award but his Jesuit performances did not satisfy critics.

He became Al Capone in “The Untouchables” in 1987. Even as his performance was criticized as shoddy, the celebrity of the baseball bat moment ensured it a lasting place in history. A switch to drama with comedic flourishes came in “Midnight Run” in 1988, combining snappy repartee and manhunting, to critical and commercial triumph.

None succeeded wholely—it had the disappointing “We’re No Angels” (1989)—but ended the decade with success in “Jacknife,” an uninspiring Vietnam drama in which he showed his unfocused range of emotions. 1990s De Niro: Master of Mobs and Mind Games

The ’90s were ushered in with his classically menacing performance as his coldly ruminative James Conway in “Goodfellas” (1990), establishing his gangster film tone. “Awakenings” (1990) followed, where he played man awakened from catatonia, his performance chilling yet compelling.

De Niro introduced animal danger to “Cape Fear” (1991) as tattooed danger with menacing drawl, Max Cady. It raked in $182 million, proof that people couldn’t look anywhere else other than at his frightful beat. masterclass Conclusion This Masterclass had De Niro in his ’80s and ’90s wasn’t an actor in the strictest sense—but Genre-Defied. What he did with his comedies, crime epics, love scenes, and dystopian horrors had no method. One wasn’t guaranteed success with each release, but failure was as enticing too. What one can learn from his time, if anything, is that De Niro didn’t compromise. He didn’t act roles—but constructed them. And by constructing them, he solidified his name as one among the greatest actors of all time.

1992–1997: A Bronx Tale to Casino: De Niro’s Defining ’90s Moments

The ’90s were a ride. Scrunchies, flanels, and what-in-the-world-was-going-on with dial-up? But all alongside that was Robert De Niro. A cinema legend who had gone from mob classics to wisecracking bro comedies to. video game development? It was a moment for risky bets, eyebrows-high outfits, and moments of sheer brilliance that only De Niro would get to do without breaking once.

1992

De Niro began the year with Mistress, a drama-comedy about screenwriters. The critics politely described it as “urbane and coherent,” which secretly means, “Yes, it’s alright, but where’s the passion?” And then came Night and the City, where De Niro again played at being a bumbling lawyer seeking another stroke of stardom. It wasn’t awful, but even the critics were not bowled over. One review stretched languidly and said, “Remember when this man was indomitable?” Savage.

He also directed Thunderheart, however, a compelling crime drama investigating Native American issues. A worthy cause, I suppose, but directors do not spend their time basking in self-congratulation.

1993

And then, but perhaps not finally, came the twinkle back once more. Mad Dog/Betrayed paired Deniro against Bill Murray in a strange bromance. Cringingly sweet watching them flub moments of friendship as Uma swooped in and scenes where she could reign supreme. And ’93’s heavyweight champ? This Boy’s Life.

De Niro was step-daddy from hell to young Leo DiCaprio, and their hatred crackled almost off the page. Chilling, subtle, indelible. And still not content with that, De Niro made his directors’ debut with A Bronx Tale, a dark drama that blends mobster hardness and Daddy-son neurosis. It plods along, I’ll admit, but critics were willing to forgive. Decent work for an inexperienced man behind the camera.

1994

Holy moly. Along comes Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Gothic melodrama devolves into gothic camp where this remake was involved, since it devolved into lightning-obsessed melodrama at breakneck speed. But De Niro’s complete dedication to tortured monster? You can’t accuse the man’s laconic. He growled, he brooded, and made electricity another payday.

1995

Peak De Niro. Casino reunited him with Martin Scorsese, and he wowed us with big suits, betraiding, and Sharon Stone’s hair-raising excellence. “Confident” said Roger Ebert, unofficially meaning “Oh, they got it just dead-on perfect.” And then there’s Heat, the crime-thriller in which he confronts one-on-one in screen legend his most legendary foeman, Al Pacino. That coffee shop chat? Flat-out cinematic lore. Two titans at their very best.

Back-to-back classics reestablished De Niro to his proper pedestal.

1996

Things went. an interesting way. Fan viewed De Niro as this wild baseball enthusiast. Wild? Maybe. Memorable? Doubtful. Along came Sleepers, as a tormented priest in a violent revenge story, then Marvin’s Room, where he ripped at heartstrings as some sort of doctor.

And yet, he still managed to create an offbeat video game called 9: The Last Resort. De Niro, video games, and talking musical instruments? Clearly, he was trying out new things.

1997

Fortunately, De Niro concluded the decade with a high. Cop Land cast him into background and as a matter-of-fact, natural, restrained performance to make room for Sylvester Stallone to revel in glory. Wag the Dog, a scathing work of political farce, teamed him with Dustin Hoffman in one of the year’s most colorful films. Jackie Brown came next, with Tarantino directing the performance by De Niro as bumbling criminal. A lesson in subtle comedy.

Verdict: Never a Dull Moment

De Niro’s ’90s were tumult, big plans, and remorselessly omnipresent at the same time. And even during his failures (hello, Frankenstein), he came at it full throttle. Mob boss, outcast, or creature man, De Niro infused every character with nuance and intensity. Some sagas boast about their excellence. Others create offbeat video games. And De Niro? Oh, he did it all. Box office bombs, smash hits, and then some account for his continued status as one of Hollywood’s most successful storytellers.

Top Ten De Niro Movies

Raging Bull

Robert De Niro in Raging Bull is not acting; he’s on a mission. To watch De Niro act Jake La Motta is to see a man haul a piano up a never-ending staircase, only to arrive somewhere and find a shattered mirror in ambush. The sweat beads, the snarl, the bruised knuckle are so melodramatically excessive that you can’t help but ask yourself, Is De Niro La Motta? Really? He’s perhaps so.

And Martin Scorsese? The man did not enjoy boxing. He only directed the film because he was pushed into it by De Niro. Flash-forward, and we have a black-and-white magnum opus chock-full of testosterone, desperation, and self-destruction. It is not a film; it is a dark indictment of man’s ugliest desires.

Schrader’s script makes Jake La Motta seethe with rage, green-eyed envy, and insecurity a pinched sausage waiting to burst. La Motta is a slob, a wrecking human. Picture a train wreck, and the whole station is crumbling behind. You don’t want to look, yet can’t avert your eyes. It is a man on fire knocking over bowling pins blindfolded.

And then there is De Niro. It’s not acting, it’s film therapy. He’s a lean, hard-hitting fighter and a bloated, self-loathing ex-powerhouse of a man who consumes his feelings ravenous-like. (Yes, he gained 60 pounds for the role.) He’s unsalvageable, and then he cracks. He’s laid bare and raw, and almost, almost, brings the abject wretch to the point of making you feel sorry for him. Almost. He’s a monster, and monsters can be lonely.

Raging Bull provides no neat solutions and comfort. The movie delivers vicious, emotional body blows and kayoes you out. You start questioning not just La Motta’s fights, but your own. Which are worth it? Which will be your scar? Indelicate and haunting, Raging Bull does not represent life—imposes life, and your reaction to its life.

GoodFellas

All due respect to Eliza Dushku’s angsty Walkman scene in True Lies, but the best application of Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” in the films belongs to GoodFellas. No debate. The raw riff isn’t establishing a tense scene atmosphere—the song is controlling the scene, dripping menace and foreboding. Imagine this: a dark, dingy bar, De Niro’s Jimmy Conway lounging cool, cigarette smoke wafting from his mouth, eyeing the room like a predator. He doesn’t move, doesn’t say a word, but you understand—he’s considering whether to take out a mob goon. He doesn’t move, but his eyes do the work. That’s De Niro scary-mellow—more restraint than fear.

Even his own bass player, Jack Bruce, mocked: “It’s the scariest scene in the film, and I’ve got my riff going in the background!” Who comes up with a riff so menacing, and turns it into a murder anthem? Some create Spotify playlists; others construct murder anthems.

This is a legend for a reason. Jimmy Conway doesn’t communicate in words. His eyes, which measure, do. The cigarette smoke, all rolled up, isn’t a release, a death notice backwards. That’s a level of tension most actors can only dream about. If suspense were a sport, and let’s say, the Olympic sport, and Conway was a competitor, he’d not only take the gold—though he’d frighten the judges for two.

And the point is—De Niro isn’t the leading man. Yet his brooding face towers over Ray Liotta’s eyes-wide Henry Hill and Joe Pesci’s eyes-a-mad Tommy DeVito. No wonder De Niro towers over the poster like a dirty ex in your messages—dirty, grimy, and can’t-look-away. Conway’s smile is his wild card, and that smirk will get you into a dark alley on the promise of a Dior sale. Spoiler: no Dior handbag, but a hit instead.

“Sunshine of Your Love” was no mere background music; that was Jimmy Conway’s theme song. Suave and lethal, smooth and sinister—just him. Combine that mood with De Niro’s self-conscious raised eyebrow and you’ve got a scene seared into the minds of every film enthusiast out there. Sorry, True Lies, but a brooding De Niro scheming murder to the rhythm of a Walkman groove fest any day!

Last lesson? Never take Robert De Niro anywhere. Sale or no sale, you’ll fail.

The Godfather II

Taxi Driver

“You talkin’ to me?” Indelible. The sentence that, for reasons nobody can explain, made a man who was sportin’ a mohawk and a code of ethics sharpened on a hotbed of insanity a cultural touchstone. Of all Robert De Niro indelibles, this one stays off the pedestal, grumbling darkly unclear and menacingly unclear things. If this insane brooding intensity cauldron weren’t emanatin’ from De Niro, he might’ve been up against a dude who’d had pineapple pizza-type thoughts on the end of human society. But no, this is De Niro territory.

Bickle is not a cab driver, he is the cab driver. A guy wading through the sludge of 1970s New York, where the wind has a hint of stale regret and steaming hot soft pretzels. He doesn’t keep human beings on a backburner in disdain; he’s a pressure cooker, clanging top onto rim. And when he blows? Bring on the anarchy, peppered with the surprise flourish of an awkwardly honest mohawk.

De Niro was not satisfied to act in Taxi Driver. He immersed himself, plunged head-first, into Bickle’s warped mind, actually drove a New York taxi back and forth to get a feel, and delivered a performance which is half tragic, half scary. He is a man crumbling under stress caused by his own contradictions. Pathetic one moment, a bigger threat than your portable’s battery meter reading double figures the next. And before you can cling on to hope that he might be saved, he reminds you why your wisest decision is not to enter his world. At its most fundamental, it is not only a Scorsese-De Niro milestone, but the template for rich social anti-heroes. Films like Joker owe a profound DNA debt to the film. Travis Bickle, all his errant self-righteousness, tortured isolation, and stomach-churning unpredictability, ratcheted up the benchmark. And somewhere, Teensploitation teens keep randomly reproducing that mirror scene. If that is not a calling card for “lasting cultural impact,” I don’t know what is.

The King Of Comedy

By the late ’70s and early ’80s, Robert De Niro was the reigning monarch of hard, tortured acting. He’d already blown critics away with powerhouse performances in Taxi Driver, The Deer Hunter, and Raging Bull. De Niro was dark, method acting at this point. So when someone was going to come along 1982 and propose his next leading man role was to be a comedy turn as a young stand-up wannabe by the name of Rupert Pupkin (yes, Rupert Pupkin), he’d more than likely have been snickered out of the room. He was going to do comedy? By De Niro? Ha!

Come on in The King of Comedy. Theoretically, it was ridiculous: De Niro as a wannabe comic who’s desperate for his moment of stardom that he kidnaps the host of a talk show. It was a parody, not a movie. But looking back, it was no laughing affair. De Niro made Rupert Pupkin a wince-worthy awkward, perilously driven man who made audiences wince vicariously. Picture the man at a party who’s got you against the wall on a speech about his “big moment” but rather than let you breathe, ups the ante on a chilling, desperate prank call. That’s Pupkin – the granddaddy of cringe comedies.

The problem with The King of Comedy is, you know, it isn’t really “funny.” It’s a sniping satire, mocking the culture’s celebrity fixation years before the era of Instagram celebrities and TikTok influencers. Martin Scorsese was mirroring the culture’s craving for celebrity, and what stared back was much too uncomfortably accurate. Pupkin isn’t a character, but an admonition dressed up in awkward mannerisms.

Flash forward to today, and The King of Comedy seems, well,more timely than ever. Its impact endures through present day dark comedies, led by Joker. That bitter fervor? That one man gone insane? De Niro pioneered it. Todd Phillips even paid homage to Pupkin’s name, Joker.

Rupert Pupkin is, rather remarkably, current as of 2023. Swap out his cassette tapes and scrapbook for viral videos and around-the-clock social media, and you have your modern-day fame monsters. The situations are different, but the hunger Pupkin represented persists today.

De Niro’s genius is making nonperforming performances cannot-forget performances. From raw anger as Jake LaMotta to manic motivation as Rupert Pupkin, De Niro doesn’t act performances; he redreams them as icons. The King of Comedy is, appropriately, a misunderstood detour on De Niro’s career, and a dark comedy masterpiece—perceptual, caustic, and indelible—next.

Because occasionally the punchline isn’t funny. It’s because folks will strain so hard just to be heard. And Rupert Pupkin predicted that punchline years ahead of the rest of us.

Heat

On paper, Neil McCauley is the one who’d be left off the dinner invitation list. When he’s not carefully casing heists more complex than Swiss clocks, he’s reading page-turners such as Stress Fractures in Titanium. And he’s got algae trivia down his sleeve. “You know about the iridescent algae up in Fuji? They come out once a year,” he schools Eady, his purported love interest. Yeah, man, he won someone over on algae trivia.

Robert De Niro walks in his spotless tidy Bally loafers (the McCauley definitely wears the same lace length for), and this human reference book of nautical and metal stress-relief items is the coolest guy in the room. With each deliberate step, there is a brooding darkness so enthralling that you can only imagine that GQ rocks a Criminal Chic look. He is stoic and deliberate, yet he makes “obsessive heist plotter” sexy.

But where is the surprise? The film’s roots are emotional granite to Neil—no crack, no fissure. But between nihilistic pep talks and hard, lengthy glares alongside Eady, love is his ruin. It is not surveillance by policemen or his “don’t get attached” rule. It is vulnerability. He cracks, emotionally, and that is all that is needed to destroy all that he has constructed. The man opens his own safe, and inside isn’t gold or gemstones, but brief moments of a soul he has kept hidden.

And now they’re releasing Heat 2. Someone is going to have to revamp De Niro’s tormented take on McCauley. But recasting a stand-in? That is not a job—this is climbing Everest in loafer shoes.

Midnight Run

What Robert De Niro actually requires is not another award on his shelf titled “Cinematic Master.” And here he is, for a midnight jaunt, not being enthusiastically and without hesitation acclaimed as one of his best efforts, is a cinematic injustice. Rather than his dark intensity, or his Italian-American machismo, De Niro takes on Jack Walsh, a bounty hunter who has the sardonic charm of traffic during rush hour—and he is delightful.

Between his gruff-around-the-edges vet in Jacknife and his smooth-talking gangster in The Untouchables, De Niro’s Midnight Run flip is utterly out of character and side-splitting funny. Walsh is cranky, always exasperated, and yet he’s so lovable of a lug that nobody is prepared. Put him with Charles Grodin’s fumbling accountant, Jonathan “The Duke” Mardukas, who did millions in Mafia embezzlement (and apologizes to inanimate objects), and you’ve got a mismatched comedy that, against all odds, does work.

This is no other buddy pic—this is buddy movie perfection. The banter between De Niro and Grodin sizzles as if they’ve been trading bon mots for decades. Their one-liners bounce off one another, ping-pong-style, and we can’t help but laugh along with them. One moment, Walsh can’t tolerate one more minute of Mardukas’ wisecracking good guy-ness; soon, they’re conspiring together to evade hitmen, mafiosi, and the FBi—why settle for a single boogeyman when, uh, three?

Even Grodin put it best: “It’s basically a guy pursuing dude, then a third guy pursuing these two dudes, then a whole new set of dudes pursuing all of them. It gets crazy.” He isn’t kidding.

And, oh yeah, this is a perfectly 80s movie. As is, that’s hi-rise jeans to infuriating payphones. But under all the fire and nutty across-country manhunts, a heart exists. Midnight Run works because, under all the fire and nutty across-country manhunts, it offers two imperfect men, brought together by muddied fate, who nonetheless make each other a better man.

If you have not watched it, what are you waiting for? Put it in your list, turn up the volume, and be treated to one sumpingly funny performance by De Niro. That De Niro, the hard-boiled, Oscar-winning hard man who dishes out sardonic one-liners by the gross. Believe me, buddy movies will never be the same again.

Mean Streets

Mean Streets was not where De Niro’s career started. The credit has to go to his very first acting stint as “Client At The Diner” in a film called Three Rooms Manhattan, 1963—datable, nearly, to the tag “future acting great.” Loitering around dirty eggs and stale coffee was obviously step one on the steps to fame. But Mean Streets? That’s when De Niro did not just enter—rather, he kicked the door wide open, smiled on his face, and said, “Get ready for trouble.”

And oh, how Scorsese brought Johnny Boy out. Subtlety? Don’t make me laugh. De Niro, however, walks in under a hail of red neon lights like Lucifer’s enfant terrible, into a sleazy bar shepherded by two women—like his wild-eyed elan wasn’t already enough. The Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” booms through the air, each riff screaming, “Trouble? Yeah, this guy.” Mick Jagger might have been the day’s hype man, but Johnny Boy was the show man. Scorsese didn’t just shoot the scene; he made the scene a slow-motion waltz of raw rebelliousness.

And poor old Harvey Keitel’s Charlie. The fellow could have claimed, “Ah, joy, here’s chaos,” because Johnny Boy tore his way through Charlie’s life like a party-loving wrecking ball. And then, man and boy, we’re hooked. Hooked on the tension, the charisma, and the trouble that De Niro emits.

De Niro is not Johnny Boy, he is Johnny Boy. Mismatched clothing (red bomber and discordant patterned shirt), superior self-assurance, and the smirk that flickers across his face that says, “Spoiled your evening, and I’ll have a good time.” A character study via clothes, posture, and swagger. And wasn’t that De Niro, the classic? He’s blown through scenes for decades, a balance of menace and suave, suspense and tension, every moment. As thug, taxi driver, or bedlam incarnate, he always shatters. And isn’t that, really, why no one can take their eyes off him?

Casino

Did De Niro ever perform any better? Possibly, possibly not. But did he ever appear any more like a fashion fever dream come to life? No. Behold Casino’s Ace Rothstein: the Las Vegas mob boss who makes all other mobsters seem like they assembled his wardrobe in the dark. This is a guy who casually opens his closet door sporting a coral-colored jacket so blindingly loud it’s visible from space. By the time he’s walking across the room in the lemon-yellow suit, just because he’s head over heels in love with the trainwreck that is Ginger (played with perfection by Sharon Stone), you know that this isn’t merely a mobster—that’s a style icon.

Ace doesn’t simply dress, he clothes. And he accomplishes it successfully. Someone compiled, on a poster, mind you, 45 of his ensembles verifying his dressing insanity lineage. But don’t think all Vegas posturing. Every seam is a creation from Ace’s imagination. Control-mad? You bet. The master moment when De Niro emerges from behind his desk, coat smooth, only to be showing bare legs underneath because wrinkled pants are, no surprise, his hill to die on. Compulsive genius? That’s not?

Ace is a half-gangster, half-tropical flamingo sashaying up and down the Vegas strip in hot pinks and lime green. Of course, he is conscious that he is stunning, but he is clueless about his arrogance being his ruin. His clothes yell, I’ve got this! as his world goes rapidly out of control. And when crash-landing is a foregone conclusion? Crushingly, but ineffably chic.

You can’t get out of a single nanosecond of destruction from Ace, and he’s a heartbreak that you weren’t aware that you enrolled for. A lesson learned through sequins, flamingo fashion, and fabricroar. Bravo, Mr. Rothstein. Bravo.

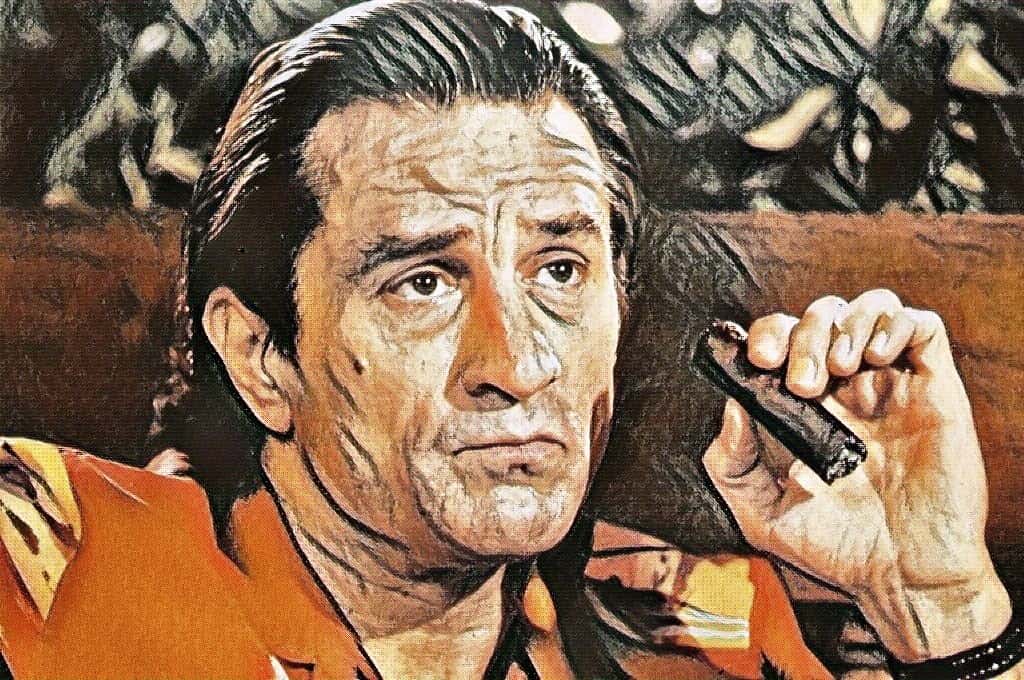

Cape Fear

What’s a greater villainous flourish than holding up a humongous cigar in a film and fog a theatre in a haze-filled hellscape and maniacally laugh? If Max Cady went no further, he’d already be the man you’d drive around on the other side of the sidewalk out of your way to avoid. But no, no, Max isn’t content to be the man ruining your day out to the pictures with his ‘smoky atmosphere’ but he’s a murdering, violent nutcase on a holy mission to persecute the Bowden family because dear old daddy, Samuel (Nick Nolte), had the temerity to get in his way. Getting a grudge on, huh.

And for goodness’ sake, is Robert De Niro simply having the time of his life ever portraying said swagging madman. The moment he’s let out of prison under a very definitely legally obligated to thunderous darkened sky, he’s all tarted out in dodgy prison tattoos, and finery is already widely known to be very definitely not on the agenda. Of course, Scorsese turns the gothic up to 11 for maximum melodrama, because everyone is going to, right? Dark, theatrical posturing. The entire production.

Yes, Max Cady’s black broad brushstrokes verge on caricature, but De Niro? He milks it for all it’s worth as if this is his defining performance. For goodness’ sake, half-expect Max to cap his killing spree by stumbling over a rake in act three. There is no rake. Is that De Niro, then? If there was, he’d made that one his Oscar moment, too.